Seniority … does it really matter?

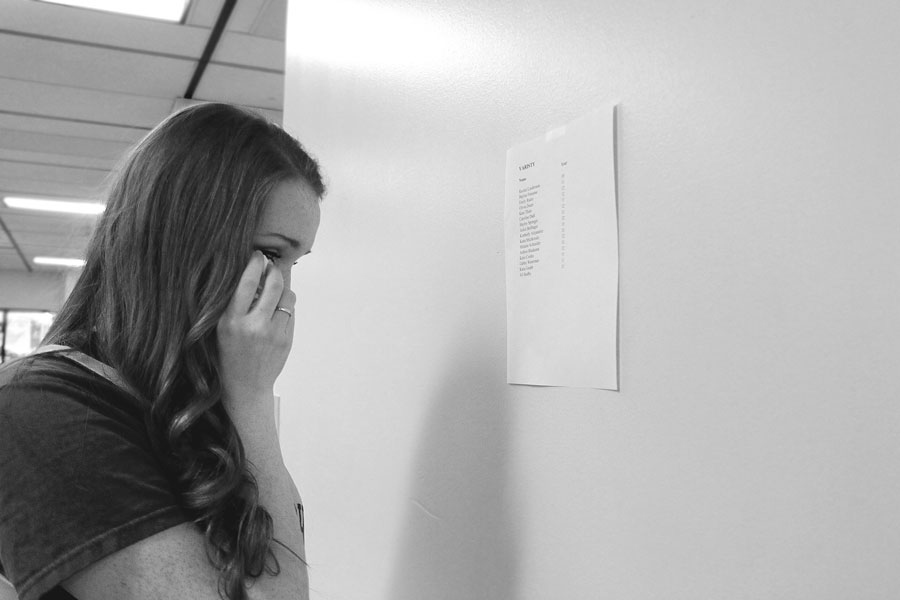

Photo illustration

Seniority. It is the reason behind why seniors get dibs on the first row of the student section at football games, why they get to ride in the back of the bus during road games, and why they get the best parking spots. But just as seniors don’t shove freshmen into lockers and football players don’t just date cheerleaders, the idea that seniority rules high school sports rosters proves to be a misconception from the interviews of Wenatchee High School athletes and coaches.

“There’s been lots of years where I’ve had to cut seniors,” said volleyball Coach LeAnne Branam. “I would rather take the best player, whether they are a sophomore or a senior. It lets kids know they don’t have a free ride in the program.”

Currently in her seventh year of coaching at WHS, she said she places skill, analyzing it through stats and video during tryouts, before a player’s number of years on a team, partly because she believes seniority doesn’t exactly equal experience.

“Leadership and experience can hold seniors in, but not always,” said Branam. “Not only does a player need to be a great worker, positive, and a leader, but they also need decent skills.”

While she won’t keep a senior if they aren’t going to play, other sports and coaches allow for different options, though the general guidelines are that a senior must make varsity, a junior must make JV or higher, etc, according to Athletic Director BJ Kuntz.

“We don’t cut based on ability or skill,” said football Coach Scott Devereaux. “I think if a person wants to play a sport, they should be able to do it. Everyone should have the experience of being on a team.”

Yet, he said only the best players play during varsity games, with the less skilled players occasionally placed on the field if possible.

Girls basketball follows a similar procedure, based on Coach Robin Kansky’s thought that “any kid can get better.”

“I try a no-cut policy,” he said. “The key is to find how a senior can give back, and sometimes that’s on the bench.”

When a senior doesn’t qualify for varsity, Kansky gives them the option to continue practicing with the team, with the hopes of them improving and possibly earning a spot on the court. However, frequently players will quit when they know they won’t take part in games.

After playing the same sport since elementary school through junior year, an anonymous senior athlete cut this fall understands the disappointment of not making the team.

“I was really excited to play with that group [this year],” they said. “It’s kind of hard to give your spot to someone younger than you.”

According to Kansky, if a player does continue to practice and earns the opportunity to play games, the reason may not be an improvement in skill.

“The three most important [things in a player] are being a good teammate, playing hard, and a positive attitude,” said Kansky. “It’s great to have talent, but if you have an attitude, it doesn’t matter.”

This personality aspect is one of the reasons why he may hesitate to put a freshman on varsity despite their raw talent, with the young player not yet accommodated to the pressure, mentality, and dynamic of the advanced level of play. Devereaux said that between two athletes of the same skill, he will put the older in to play with the more experience on the advanced team, though the younger player has the chance to pass him through improvement.

One player that Branam said was physically but not mentally ready for the varsity level as a freshman was senior Rachel Leiber. With her time on varsity dating back to sophomore year (not counting being brought up for varsity games as a freshman), she knows what it’s like being the underclassman under the bright lights, though is also aware of those players in a different situation.

“When they [the setters] are setting the the older players more than you, you are thinking, ‘What the hell?” said Leiber. “[When it comes to seniority], some players are selfish, and they want to be on a team. They are thinking, ‘I’m a senior, why the hell am I not on varsity?’”

For freshman varsity cross country runner Moses Lurbur, he hasn’t had much experience with biases based on grade level due to how cross country teams are built on runners’ times.

“You can crunch the numbers and tell who will be on varsity,” said Lurbur.

As the only freshman runner on varsity cross country, Lurbur said he was surprised to have made it so far; however, some athletes aren’t moved by the placement of underclassmen on varsity.

“[Coaches] look at potential and physical traits, not necessarily skill at the time,” said an anonymous player who was recently cut.

According to them, the unfairness in assessing athletes in high school sports isn’t seniority but favoritism.

“The coach and the players were acting buddy-buddy [during tryouts], and I was over there working my butt off, and they didn’t even know my name,” said one athlete.

On the other hand, some players will tell you work ethic dictates your future on a team.

“First they look at the hardest working players, then the years played,” said senior football player Max Gould.

According to Kansky, all decisions are based on the goal to benefit the team and the idea that varsity is expected to win. With that, the coaches agree no player is guaranteed a jersey.

“You are always going to have to compete,” said Devereaux, “no matter if you are a four year player.”